Increasingly, I’m coming to the conclusion that not only is the way that we develop land an inefficient use of space, it’s also bad for us.

To start with some context, let’s consider how the way that we build houses has changed, particularly since the 1960s and ‘70s, the heyday of the quarter acre dream. Kiwi have long preferred detached housing. I suspect this is largely because of an abundance of land to develop, though the fact that a lot of our population growth has occurred in the age of automobiles is undoubtedly a contributing factor.

For much of the twentieth century, we built relatively modest houses on relatively generous sections. The infamous quarter acre plot was the standard, approximately 1000 square metres (sqm). On this the average house built in the 1970s was a little over 100 sqm, leaving ample space for veggie gardens and makeshift cricket pitches. It’s also worth noting that fences were rare, or small, creating an environment conducive to interaction with neighbours.

Fast forward to 2010, and the average new section had nearly halved to 500 sqm, while the median new house size was 205 sqm [1]. While it’s worth noting that the median new house size has dropped back a little in the last decade, mostly due to cost pressures, the point remains that we are now building relatively large houses on relatively small sections.

This seems counter-intuitive; in the same time the average family size in NZ has decreased from 4.6 to 2.7 [2,3], so we have smaller families but bigger houses. And all of this comes at the expense of outdoor space for living.

Our housing choices have been shaped by changes in our national culture as it has become more individualistic. The large houses we now build, surrounded by high fences, are representative of our ideological prioritisation of the private over the public.

However, as Winston Churchill said, “we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us”. Our society has influenced the way we build houses, but now the way we’ve built houses is influencing our society. We’ve weakened our connection with our local communities, while ironically, in the age of Covid-19, we are coming to understand the true value of strong communities and local support networks.

Closed off from the world in our private castles, behind high fences, we’re far less likely to socialise with the neighbours. We might know their names, but any meaningful social interaction is unlikely. Our kids probably don’t play together as they might in the absence of those fences.

At the same time we’ve lost access to the outdoors. Most new sections aren’t really big enough to have meaningfully useful outdoor areas. A lot of people now drive to the nearest park to walk their dogs or kick a ball around.

The reason this is important, is that both social interaction and time spent outdoors are linked to better mental and physical health outcomes. There are a plethora of studies on the value of social contact, linking it with everything from reducing stress and anxiety, to preventing cognitive decline, to helping us live longer and fight disease [4]. Likewise, time spent outside has been linked with a range of benefits, including improved mental health and better brain function [5]. Alongside this there are the obvious benefits from more exercise and vitamin D.

Alongside the mental and physical health challenges our society faces, we should also consider the housing shortage, escalating building costs, and the fact that our towns and cities are sprawling outwards, eating into our productive land at an alarming rate. We need to find a way to build more houses, more cheaply, without taking up so much land. Yet also we must foster strong communities and enable better access to outdoor spaces.

While better quality infill development and inner-city apartments are undoubtedly part of the solution, greenfield subdivisions provide a significant proportion of our housing. Developers, architects and local authorities have a responsibility to ensure we are making the best use of any land that we give over to residential development.

I suggest that a part of the solution is a mindset change. We should re-imagine subdivisions as a group of micro-communities, rather than a set of individual properties and houses. For example, rather than planning how to divide land into 200 sections, what might change if we instead planned 20 or 25 small communities?

There is no one-size-fits-all solution, and what works in Te Awamutu might not be appropriate for a development in Auckland. However, this could mean:

- Building smaller houses on smaller sections, as well-designed communities shouldn’t need as much private space;

- Mixing housing typologies and sizes to encourage more diverse communities;

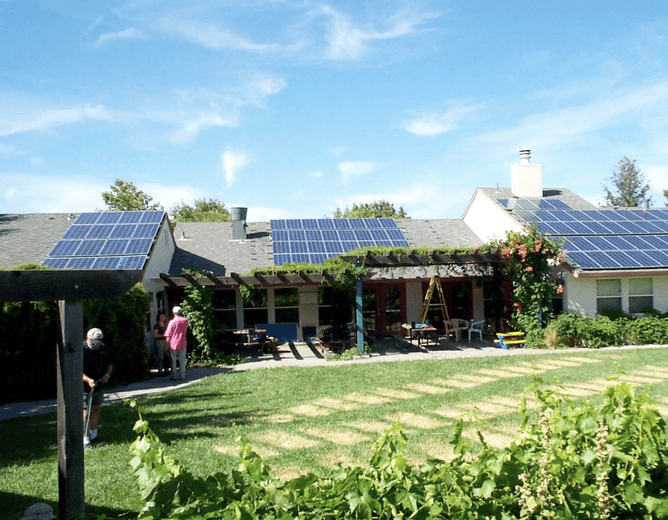

- Providing more outdoor public spaces at the hyper-local level, e.g. small parklets or shared backyards, community gardens, orchards, allotments, perhaps even pools shared between several properties;

- In some cases taking the community thinking a step further, to create co-housing communities;

- Rethinking our roading networks to fit around a community development model, providing more quiet streets and safe pedestrian and cycling routes, without reliance on cul de sacs.

The last few years have already seen some drop-off in the size of new houses [1], reflecting concerns about the cost of building. As our towns and cities eat up progressively more productive land, it’s imperative that we consider how we can incorporate more density to our residential developments without sacrificing quality of life. Designing with the goal of creating small, vibrant communities is one part of the solution and at least, a step in the right direction.

Article by Phil Mackay

Links and further reading:

1. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/new-homes-around-20-percent-smaller

2. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41601098 The New Zealand Family: Present Trends (BENJAMIN SCHLESINGER)

4. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321019#Face-to-face-contact-is-like-a-vaccine

5.https://healthmatters.wphospital.org/blog/january/2021/my-doctor-told-me-to-get-outside/